Nell’anno appena trascorso, il 2024, è stato celebrato il bicentenario della morte di George Byron di cui è difficile scrivere qualcosa che non sia stato già scritto. Considerate poi le numerose biografie che lo riguardano: si corre il rischio di rinarrare l’eroe romantico, il poeta avventuroso dall’indiscussa fama di seduttore, il padre di tre figlie, paternità (pare) però attendibili solo per due bimbe, e le complicate relazioni con le diverse madri.

George Gordon Byron si conferma artista talentuoso, dall’esistenza tumultuosa, amaramente amputata dalla morte, avvenuta a trentasei anni, a causa di una meningite, morte forse simbolo di incompiutezza e testimonianza di infelicità. Ma se è caro al ciel colui che muore giovane, come recitava Menandro, la fama di Byron risulta ben meritata: è stato fra i maggiori rappresentanti della poesia inglese dell’Ottocento ed intellettuale di spicco nel Regno Unito durante il secondo Romanticismo. Ha viaggiato a lungo per l’Europa, in paesi diversi, legandosi in particolare all’Italia e alla città di Ravenna, dove visse e si spese nelle molteplici vesti di politico, poeta e compagno della giovanissima contessina ravennate Teresa Gamba Guiccioli.

George Gordon Byron nacque nel 1788 a Londra, frutto dell’unione fra il capitano John Byron, soprannominato mad Jack, ovvero Jack il pazzo – che in vita contrasse infiniti debiti, pare tristemente saldati in Francia con una morte suicida – ed una giovanissima Catherine Gordon, donna umorale e collerica, che alternava aspre rampogne ad improvvise quanto imprevedibili tenerezze. Nella capitale inglese trascorse però poco tempo: passò l’infanzia per lo più ad Aberdeen, in terra di Scozia, in compagnia della madre, afflitto da una zoppia legata ad un problema di natura tendinea. A nulla valsero i tentativi, numerosi, di correggere quel difetto fisico, ovvero la contrazione del tendine di Achille che lo portava a zoppicare. Per quanto mascherata da una sorta di andatura originale, la zoppia causava a George un’enorme sofferenza psichica, facendolo sentire tremendamente diverso dagli altri. Pesarono inoltre le ristrettezze economiche della famiglia: solo la morte di un prozio permise il viraggio verso una esistenza agiata e rassicurante, evitando così al giovanissimo Byron una vita che probabilmente avrebbe potuto essere povera, forse anche piatta ed incolore.

Il 1798 segna quindi una significativa svolta: eredita dal prozio beni consistenti, un titolo nobiliare e diventa così il sesto barone Byron di Rochdale ovvero un Lord. Potrà finalmente permettersi un’adeguata educazione e abbandonare Londra per Newstead, entrando in possesso di vaste tenute. Nel 1801 inizia a frequentare la Harrow School nella quale si distingue per un’ insaziabile amore per la lettura, ma anche per una condotta intemperante e trasgressiva. Apparterranno agli anni successivi amicizie, amori e legami profondi sia con Mary Ann Chaworth, lontana cugina, sia con John Edleston. Quest’ultima relazione verrà segnalata addirittura come omofila, uno fra i motivi, tanti, che spingeranno in seguito Byron a lasciare l’Inghilterra e a viaggiare a lungo e spesso in Europa.

Nel Settecento, ma anche nel secolo successivo, il turismo culturale per un letterato britannico rappresentava anche un vero e proprio tour di formazione, diventava l’humus dal quale trarre spunto per l’esercizio della scrittura: oltre a mostrare affezione per il diverso e il non usuale, il viaggio di per sé permetteva allo scrittore inglese di intrecciare relazioni con politici e uomini di cultura italiana del tempo. Con dovizia di particolari lo raccontano Baldini e Bolognesi (E. Baldini e Dante Bolognesi, Il richiamo di Ravenna. La città e i suoi dintorni secondo i visitatori stranieri, 1800-1960, Longo, Il Portico, 2015), offrendoci pagine ricche di vicende anche bizzarre, di passioni intense , di interessi molteplici e di rare curiosità.

Non solo quindi il legame con Edleston, morto giovanissimo, divenne oggetto di profonda riprovazione da parte dell’opinione pubblica britannica: molte furono anche le critiche per la relazione con la sorellastra Augusta, conosciuta dal poeta solo in età adolescenziale, dalla quale pare abbia avuto nel 1814 una figlia, Medora, che assumerà il cognome Leigh, marito di Augusta. Il legame con Augusta si manterrà forte e profondo nel tempo, lo confermerà la lettera inviatale a marzo 1819 da Venezia.

Amor mio, ho trascurato di scriverti, ma che dirti?! Lo stare lontani per tre anni, un cambiamento totale di luoghi e abitudini, ci ha portato a non condividere nulla, tranne affetti e legami. Non ho mai smesso né potrà accadere di provare altro che un legame, profondo, che unisce e unirà entrambi togliendomi così la possibilità di provare un amore vero per qualsivoglia altro essere umano.

Meno di tre mesi più tardi, a giugno 1819, travolto dalla passione per la contessina Gamba, Byron deciderà di abbandonare Venezia per Ravenna: sarà il triennio 1816-1819 a segnare un solco profondo nel viraggio esistenziale che seguirà al soggiorno italiano. Il 1816 sancisce la separazione dalla prima (ed unica) moglie, lady Milbanke, dalla quale aveva avuto la figlioletta Ada. Scarsissimi o addirittura nulli saranno nel futuro, per espressa volontà di Lady Milbanke, i rapporti con la bimba.

Lady Milbanke, che in un primo tempo respinse le profferte amorose del poeta, proveniva da una famiglia aristocratica, era dotta e religiosa, portata per la matematica, tanto da venir scherzosamente soprannominata dal marito principessa dei parallelogrammi. Fu lei a rompere definitivamente il legame con Byron quando, incinta, apprese del rapporto incestuoso che il marito intratteneva con la sorellastra Augusta.

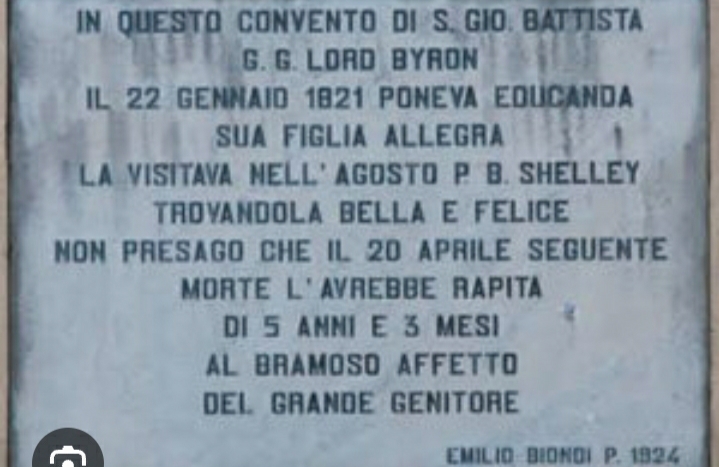

Nel 1817 nasce la seconda figlia di Byron, Allegra, una bimbetta che ebbe vita breve ed una morte infelicissima a causa, pare, del tifo contratto mentre cresceva nell’educandato delle Suore Cappuccine di Bagnacavallo dove il padre l’aveva allocata, contro il volere della madre Claire Clairmont.

La giovanissima Claire, poco più che diciannovenne, era straziata per la lontananza dalla figlia e addolorata per l’insensibilità imposta da un patto/baratto crudele, espressamente voluto da Byron. Claire avrebbe dovuto rinunciare a qualunque contatto con la piccola Allegra e Byron si sarebbe assunto l’impegno di provvedere all’educazione della figlia, che doveva crescere come una vera Byron. Claire in quel periodo non disponeva di mezzi di sostentamento sufficienti per sé e per Allegra: irretita dal fascino che aleggiava intorno al poeta e al tempo stesso non volendo rinunciare alla vita con la figlioletta, lottò per quanto le fu possibile per trovare un accordo meno disumano. Bene lo racconta Manuela Mazza (Claire Clairmont Epistolario – A cura di Manuela Mazza, Ed. Solfanelli, Chieti 2014) nel suo toccante testo. Claire provò più volte, e disperatamente, a convincere Byron a mutare avviso ma fu costretta ad arrendersi. La piccola Allegra cresceva nel frattempo senza figure di riferimento autorevoli e amorevoli, più o meno affidata alle cure di governanti, di domestici forse anche affettuosi, non mancandole la gentile attenzione della contessina Gamba, con la quale il padre ebbe una relazione profonda che durò fino alla morte del poeta avvenuta nel 1824. Sulla vita di Allegra si sono spese pagine molto belle (Iris Origo, Allegra, la figlia di Byron, Skira, 2014) e forse rappresentano una delicatissima forma di risarcimento (postumo) per un tempo di vita amaramente amputato. La bimba crebbe comunque vivace e gioiosa, ma agli occhi del padre altro non era che un grazioso giocattolo, magari una piacevole creatura, certamente vezzosa, con tratti caratteriali e fattezze che richiamavano l’origine byroniana, ma che alludevano inesorabilmente all’esistenza di una madre, peraltro drammaticamente lontana. Allegra era suo malgrado diventata l’oggetto della contesa fra due genitori, il territorio dove la rabbia e l’intransigenza di entrambi si erano guadagnati un ingiusto spazio.

Se Claire non si rassegnava ai continui rifiuti, continuando a mostrarsi comunque invaghita, Byron rifiutava il frutto del legame, con un puntiglio sprezzante e tenace. Tutto sommato si comportava come se volesse cancellare con l’allontanamento di Allegra l’esistenza della fugace relazione avuta con Claire e dunque una forma di responsabilità afferente alla propria paternità. Un faticoso e paradossale compromesso venne conquistato non solo ponendo fine alle istanze amorose di Claire e alla sua volontà di costruire comunque una famiglia che includesse la bimba, ma barattando l’esclusione della vita della bimba da quella di entrambi i genitori con l’affidamento della piccola alle Suore Cappuccine di Bagnacavallo. Luogo nel quale né padre né madre si recarono a fare visita ad Allegra: solo l’amico comune Shelley, che si era in qualche modo affezionato a questa creatura, si recò qualche volta ad incontrarla.

Manuela Mazza, nel suo delicatissimo Epistolario, ha saputo ricreare quell’atmosfera particolare fra Claire e George, ci ha trasmesso i momenti del corteggiamento, le lusinghe che adottava la donna per frequentare Byron, le velleità della stessa, un sottaciuto sgomento generato dai continui rifiuti che le opponeva Byron e, soprattutto, il tormento interiore per non poter provvedere con propri mezzi alle necessità della sua bimba. Un testo che permette, attraverso un plot narrativo strutturato nella felice formula dell’epistolario, di intuire in profondità quanto Byron fosse ben lungi dall’assumersi una benché minima responsività a livello genitoriale e quanto intima ed intensa fosse la sofferenza sulla quale s’ avviterà la vita di Claire.

Il suo epitaffio concentra dolore e senso di colpa che per volontà della defunta doveva suonare monito e rimprovero, scolpito sulla tomba nel Cimitero della Misericordia di S. Maria in Antella, a pochi chilometri da Firenze.

She passed her life in sufferings, expiating not only her faults, but also her virtues.

(NdR.: liberamente tradotto in Passò la vita espiando non solo colpe ma anche virtù)

Il poeta inglese George Byron giunge a Ravenna, una città addobbata a festa per la ricorrenza del Corpus Domini, il 10 giugno 1819. Un arrivo che non passa inosservato perché la carrozza, che Byron si era fatto costruire, sul modello napoleonico, conteneva un lettino, una libreria, un forziere ed un servizio da tavola. Su invito del Conte Guiccioli, il marito di Teresa, conosciuta ad aprile a Venezia, e dietro il pagamento di un congruo affitto, il poeta britannico si insedia al primo piano di Palazzo Guiccioli, in compagnia di una nutrita schiera di animali oltre, ovviamente, a numerosi domestici.

Dieci cavalli, otto enormi cani, tre scimmie, cinque gatti, un’aquila, un corvo ed un falco, che, come notò l’amico e poeta Shelley, in visita due anni dopo , si muovevano indisturbati per casa, protagonisti di reciproci alterchi, cui pare assistessero anche cinque pavoni, due galline faraone ed una gru egiziana che per lo più stazionavano sulla scalinata del palazzo.

Se l’amico Shelley non riuscì a nascondere il proprio stupore, gli stessi ravennati rimasero sconcertati apprendendo in modo casuale dell’esistenza di cotante presenze: risultò ulteriormente amplificata la fama che circondava un letterato tanto bizzarro quanto colto e originale. Difficile stabilire il ruolo vero assunto dal πρόσωπον, termine che in ambito teatrale mantiene nel greco classico l’accezione di “faccia” o “maschera”, attuando così il nascondimento della persona: con molta probabilità Byron nutriva il suo personaggio proprio dei demoni che lo tormentavano, dell’inquietudine che gli causava il vivere, soprattutto dell’irrequietezza, non priva di un’autoimposta solitudine, che esercitava, su molte donne del tempo, potente fascino e forte attrattiva. In qualche modo la fama del personaggio veniva alimentata dal tormento stesso della persona e gli attirava numerose critiche e non mancando dunque l’inevitabile gossip il poeta inglese era al centro della scena di un paesotto quale possiamo immaginare Ravenna agli inizi dell’Ottocento. Dal canto suo Byron, talvolta infastidito dai pettegolezzi locali, ricambiava con negligente fastidio le provocazioni malevole, contribuendo ad enfatizzare ulteriormente la fama di personaggio originale.

Ai commenti non benevoli ed al neanche tanto celato sconcerto dei ravennati Byron restituiva una sobria quanto calcolata indifferenza, atteggiamento che se da una parte rintuzzava chiacchiere e pettegolezzi, dall’altra contribuiva a far crescere giorno per giorno quell’alone di fascino e mistero che circondava il poeta inglese. Una bizzarra trasgressione non si sposava allora facilmente con quel senso di stabilità e obbedienza dettato dalla tradizione locale, ma ogni regola, tradizione inclusa, per quanto tutelata e tutelante, esigeva, quasi in una sorta di controcanto, la dovuta eccezione. Scriveva infatti Byron a Richard Belgrave Hoppner, nel gennaio 1820, pochi mesi dopo il suo arrivo a Ravenna:

Mi sto allenando molto duramente per imparare a piegare uno scialle (…) qualche volta mi confondo (…) e metto tutti i cavalier serventi in agitazione (…) si tratta di un luogo terribilmente moralista (Ravenna), infatti non si può badare alla mogli di chiunque (…) e se si passa alla porta successiva si è biasimati e considerati infidi (…). La relazione dell’amante ha tali e tante regole (…) perché dall’amante le donne locali esigono fedeltà come un debito di onore.

Soprattutto dichiarava apertis verbis quanto poco sopportasse sia le costumanze locali sia il conflitto che sovente gli accadeva di avere con l’autorità esercitata dal potere politico ravennate.

Oltre alle vessazioni di cui ti parlavo (…) sono incorso in una lite con i carabinieri del papa o meglio con la sua gens d’armerie, che hanno fatto una petizione al cardinale perché le livree dei miei servi assomigliano troppo alle loro maledette uniformi. Fanno obiezione particolare alle spalline, che da noi tutti sfoggiano nelle occasioni di gala. Le mie livree sono di colore conforme al mio stemma, lo stesso che distingue la famiglia dal 1066. Come puoi ben immaginare ho mandato una risposta tagliente: ho fatto capire che se un soldato di quel rispettabile corpo insulta i miei servi mi comporterò allo stesso modo con i loro comandanti. Ho dato ordine alla mia marmaglia, sei di numero e passabilmente agguerriti, di difendersi in caso di aggressione: nei giorni di vacanza e gran festa armerò l’intera squadra me compreso (…). Tutte queste faide comunque fra il cavalier per via di sua moglie e le truppe per le mie livree sono molto noiose per un uomo tranquillo che fa del suo meglio per compiacere il mondo intero e non desidera altro che amicizia e benevolenza.

Va premesso che Ravenna, pur oggetto delle visite di scrittori e poeti inglesi, non rappresentava nell’Ottocento affatto una meta usuale, perché era anche difficilmente raggiungibile. Enclave ostica o luogo di suggestioni, rimaneva comunque discosta rispetto a mete più tradizionali e famose quali Venezia, Roma, Napoli e Firenze. Scelta nel lontano V secolo d.c. come capitale dell’Impero romano d’Occidente, confermerà nel tempo quanto la posizione isolata e circondata da paludi, molto difficilmente espugnabile, sarà in grado di offrire sicurezza. Cionondimeno il soggiorno byroniano vivacizza questo luogo, si creano amicizie, legami e, soprattutto, nasce una partecipazione attiva alla vita politica del tempo: il poeta diventa un carbonaro americano mettendo a disposizione la propria dimora come deposito delle armi per i carbonari ravennati.

Fin dall’inizio del suo soggiorno la relazione con la contessina Gamba darà stabilità al suo essere ondivago: dopo un impatto alquanto disorientante Byron finirà per conquistarsi una sorta di benevolenza della gente del luogo, una popolazione da lui definita stranamente schietta, eccessiva quanto pugnace. Per Byron i romagnoli erano addirittura i migliori mercenari si potesse trovare e non lo stupivano neanche gli omicidi fra i locali, uccisioni usualmente quotidiane, perpetrate alcune per passione amorosa, altre per interessi legati a proprietà.

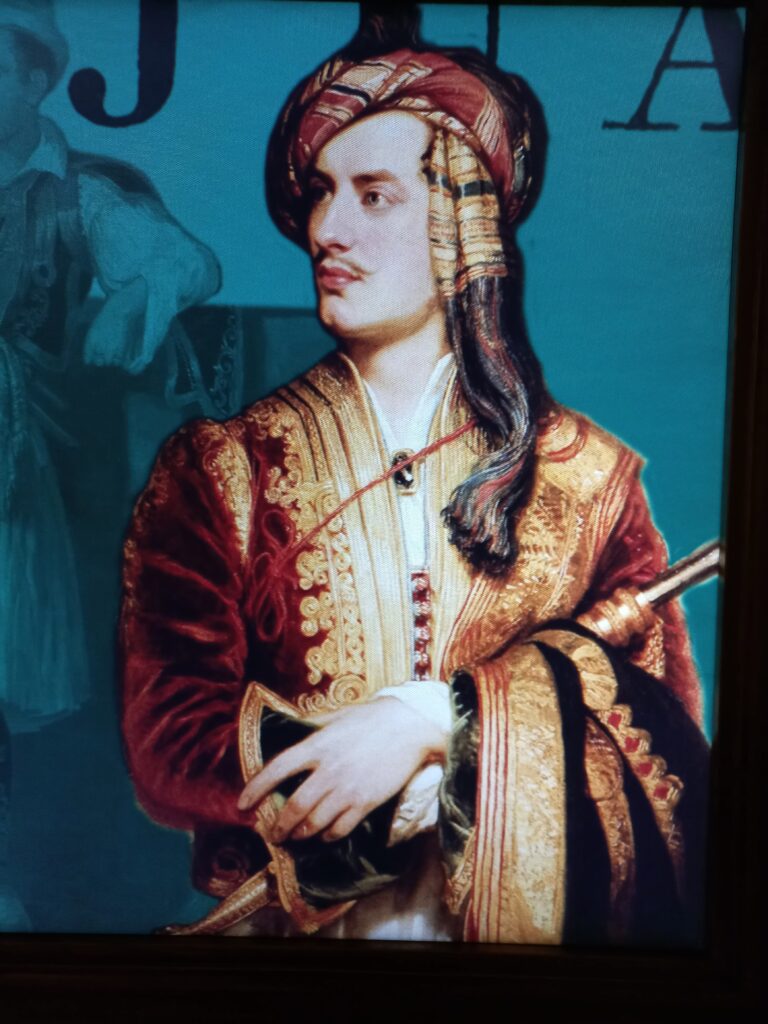

Originale e generoso, intemperante e insofferente di ogni forma di autorità, ma pervaso da sentimenti profondi di libertà e giustizia per i più deboli, Byron confermava appieno, con azioni e comportamenti, quel tratto di originalità che le sue biografie ci hanno da sempre tramandato. L’amore per la scrittura di cui si nutre tenacemente non lo abbandonerà mai: nel silenzio della notte nascevano le sue immagini narrative e dal ricordo di Dante Alighieri e di Giovanni Boccaccio coglieva recondite suggestioni. Amante della natura e della pineta, dove cavalcava spesso, anche in compagnia della contessina Guiccioli, frequentava al contempo con assiduità i salotti locali, dove veniva corteggiato, omaggiato, anche vezzeggiato per i suoi abiti eleganti e preziosi, lui rappresentante vero del dandismo.

In una delle lettere scritte ad Augusta Leigh, nel luglio del 1819, tutto sommato ammetteva di aver trovato una sorta di pacificazione, di sentire che qualcosa lo placava e dunque in qualche modo riscuoteva il suo interessamento. In buona sostanza pare davvero vivesse quel tempo di vita con un senso di coinvolgimento più intenso, mancato ai giorni del suo passato.

Ho i miei cavalli, e si fanno splendide galoppate nella foresta, e poi ho anche la mia carrozza, e il mare, e i miei libri, e questa signora; così il tempo passa. Mi piace molto cavalcare, mi è sempre piaciuto fuori dall’Inghilterra: odio i vostri Hyde Park, e le piste, ho bisogno di boschi, pianure o deserti in cui spaziare, mentre detesto conoscere in anticipo la strada da percorrere o venire interrotto dalle vostre dannate indicazioni stradali, o da un villano che strepita pretendendo due pence a un incrocio o davanti ad uno steccato.

Anche il ruolo di cicisbeo, usanza amorosa del tempo, tutto sommato lo incuriosisce: pur avvalorando il suo mondo e le origini inglesi come le migliori, non riesce a non farsi meticciare dai costumi locali. Non manifesta imbarazzo, tanto meno appalesa un ostile rifiuto, piuttosto si barcamena dentro una benevola e quasi accondiscendente curiosità. Pur biasimando l’inconsistenza della figura del cicisbeo, vi si conforma, almeno in apparenza: in questo modo mima una forma di adattamento che gli permette di ingraziarsi il favore delle dame e di non inimicarsi troppo i rivali in amore. Il cicisbeo infatti altro non era che una sorta di cavalier servente totalmente dedito alla dama con la quale aveva intrecciato la relazione amorosa, col tacito consenso del marito (della dama stessa). Non si trattava quindi di un banale damerino, meramente premuroso: era un paggio gentile, dalle costanti attenzioni, una figura molto significativa nel triangolo amoroso che vigeva al tempo. L’unica condizione posta era che non venisse stravolta la sostanza di tale forma di triangolo amoroso: non doveva insinuarsi fra la dama e il cavalier servente un sentimento forte e vero, capace così di affondare l’insignificanza del precedente legame matrimoniale. All’inizio Byron vi si adeguò ma quando la passione per la contessina ravennate si trasformò in un più forte e coinvolgente sentimento, anche per evidenti affinità di interessi di entrambi, le carte vennero per così dire sparigliate e Teresa Guiccioli chiese la separazione dall’anziano marito, separazione concessa a condizione però che la contessina rientrasse nella casa paterna.

Byron è stato un uomo tormentato, conteso e sfuggente, si portava intimamente una tempesta interiore e un’insoddisfazione foriera di inquietudine. Forse diventa facile supporre mascheri meglio di altri la persona dentro l’arcinoto personaggio perché la sua esistenza, pur breve, sembra di per sé un paradosso: lo dichiara lui in primis nel 1812 affermando di essersi svegliato già celebre proprio il giorno successivo alla pubblicazione dei primi due canti di Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

Il soggiorno di Byron in Ravenna è anche in grado di dirci molto dell’anima ravennate, che Byron interpreta a suo modo: la vive negli eccessi e nei respingimenti, se ne allontana davanti alle costrizioni , diventa partecipe nel promuovere attenzione per le lotte politiche.

Nel carteggio con John Murray risponde in modo aperto ed enigmatico al tempo stesso alla sua richiesta di un libro sui costumi degli italiani: può darsi che io ne sappia più della maggior parte degli inglesi perché ho vissuto in mezzo a loro e in alcune zone del paese dove mai degli inglesi avevano vissuto prima. Parlo soprattutto della Romagna e in particolare di Ravenna ma per molte ragioni non me la sento di pubblicare qualcosa su questo argomento. Ho vissuto in casa loro, nell’intimità delle loro famiglie, a volte semplicemente come amico di casa, a volte come amico del cuore della dama, e in nessun caso mi sento autorizzato a scriverci sopra un libro. La loro morale non è la nostra, la loro vita non è la nostra, i modi di pensare, di vivere sono così radicalmente diversi che io non saprei proprio come illustrare un popolo che è insieme sobrio e scialacquatore, serio nell’indole ma buffone quando si diverte, capace di impressioni e di passioni improvvise ed insieme durevoli ,cosa che non si trova in nessun altro paese e che per il momento non ha una società come si può vedere dalle loro commedie.

Eppure, come ebbe poi a sottolineare la stessa Yourcenar: (…) non c’è altra città dove si risenta maggiormente dello iato tra interno e esterno, tra la vita pubblica e la segreta vita solitaria.

La città di Ravenna diventerà, fra conflitti e amori, comunque un luogo del cuore e della mente nella personalità di Byron, prima della morte avvenuta nell’aprile 1824 in Grecia. Forte la passione politica che lo porta ad aderire alla carboneria, favorita dall’amicizia con Ruggero, padre di Teresa e con Pietro Gamba, entrambi cospiratori. Byron entrò nella setta carbonara dei cacciatori americani, partecipando con la consueta generosità alle riunioni segrete. Alimentava così non solo la leggenda di un’amante appassionato, ma anche quella di uno spirito libertario, che oltre a sostenere le cause locali sacrificherà in nome e per conto della libertà gli immensi vantaggi della propria condizione, fortuna e genio. Non verrà mai meno durante il periodo ravennate neanche al legame stretto con la sorella naturale, soprannominata Gus, frutto della precedente unione del padre Jack, anime le loro rapitesi vicendevolmente, in qualche modo complementari l’una all’altra. Augusta, fu, con Teresa Guiccioli, la donna che seppe meglio trasmettere la semplicità di un calore familiare di cui lo scrittore necessitava. D’altro canto quella forma di instabilità e irrequietezza, tratto saliente della personalità del poeta, lo portavano sempre altrove, lo spingevano alla ricerca di luoghi nuovi e incontri non consueti, ma erano anche la molla più potente che lo portava a scrivere nella forma frequente della autorappresentazione.

La città di Ravenna viene spesso associata alla vita del poeta, soprattutto in questo trascorso 2024 che segna il bicentenario della morte del nobile inglese, tanto che l’immagine ravennate nella quale si omologa facilmente Byron pare anche troppo scontata e sembra esaltare piuttosto la temperie di un tempo (troppo?) passato che pare quasi insistere nel volersi intrecciare col proprio passato prossimo. Il miglior narratore di un luogo è sempre il viaggiatore che, a differenza del turista, riesce a ricambiare quella sorta di dialogo muto, ma eloquente al tempo stesso, che si instaura fra gli occhi che guardano e le cose quando sono viste.

Poche città in Italia offrono più oggetti di interesse per un antiquario, un filosofo, un poeta di quanto faccia Ravenna, ma la sua posizione geografica, che la colloca al di fuori delle vie più battute, fa che sia evitata dalla massa generale di stranieri che percorrono altre parti di questa bellissima terra. L’inglese più di qualsiasi altro popolo porta con sé l’abitudine del proprio paese: sembra che non viaggi tanto allo scopo di studiare i modi degli altri ma piuttosto per difendere e mostrare i propri.

Letterato, poeta, ma soprattutto uomo d’azione, attento a quello spirito di scontento ed insubordinazione – che covava sotto le ceneri e talvolta s’infiammava in improvvisi incendi – Byron partecipava alla lotta politica facendo proprio il senso di ribellione e il bisogno di giustizia di coloro che gli erano accanto. Il Byron letterato non si discosta dal Byron politico, si interfaccia con la vita che è lotta, combatte e partecipa da sodale.

Negli ultimi anni, in particolare nel periodo della visita di cui sto scrivendo, tutto il distretto e la Romagna in generale sono state la parte d’Italia più inquieta e ribelle. Libertà giustizia e fraternità (…) si esplicitano in una anomala quantità di crimini e di insicurezza per cui hanno molto attecchito.

Esiste poi, ed in qualche modo Byron lo sottolinea, un contrasto fra la città della vita e la città dei ricordi, dei monumenti del passato, tra la città che si percorre, in cui si vivono i pochi o molti giorni del viaggio e in cui gli abitanti vivono la loro esistenza umana, e la città nascosta, quella per la quale si è compiuto il viaggio, quella letteraria. Di questa antinomia sono piene le pagine di scrittori e poeti che hanno dedicato le loro opere a Ravenna. Impossibile non ricordare Gabriele D’Annunzio che scrisse ben due liriche su Ravenna, incastonandola nella memorabile serie delle città del silenzio. Il passato che abita Ravenna viene da lontano, da un mondo col quale non c’è più contatto (…) Ravenna sussurra l’intima essenza della solitudine di un mondo talmente desolato che solo il sole la nebbia e il vento sembrano essere di casa .

Tutti i vantaggi della modernità non hanno comunque tolto gran parte di quella profonda poesia che toccò il cuore di Dante e di Byron. Ma per Byron forse quei fantasmi non erano parte della malinconia del ricordo della città nascosta, erano parte della città viva: davvero il poeta inglese rappresenta il nuovo atteggiamento di chi guarda il mondo da ed entro Ravenna. Trova in Dante forte consonanza, comunanza di sentire e di destini. Come Dante, Byron aveva dovuto lasciare la patria anche se per lui, esacerbato dalle critiche per la sua condotta di vita, si era trattato di una scelta volontaria. Ma l’Italia continuerà a piacergli e Ravenna rimanere luogo del cuore.

Con tutti i suoi peccati devo dire / che l’Italia mi piace che mi piace

vedere il sole splendere ogni giorno / e le viti non piantate su un muro

ma abbarbicate ai tralicci fondi / d’opera dove la gente accorre

quando una danza chiude il primo atto / tra vigne rosseggianti come in Francia

(Keats, Shelley, Byron, I ragazzi che amavano il vento, a cura di Roberto Mussapi, Feltrinelli, Milano 1996)

di Rita Farneti

L’autrice rivolge un sentito ringraziamento alla casa editrice Solfanelli per la cortesia e disponibilità dimostrata. Altrettanto sentito ringraziamento è rivolto al personale della Biblioteca Oriani di Ravenna per la gentilezza e premura nella messa a disposizione di testi molto rari durante la ricerca, e all’Ufficio Stampa di palazzo Guiccioli, riaperto – dopo un sapiente restauro –il 19 aprile 2024 in occasione del bicentenario della morte di Byron; al suo interno, il 29 novembre 2024 è stato inaugurato il Museo Byron e del Risorgimento.

www.palazzoguiccioli.it/ilpalazzo/

Immagine di copertina: Studiolo di Byron, palazzo Guiccioli, Ravenna – www.palazzoguiccioli.it

—————————————————————————————————————————–

VERSIONE INGLESE:

With the eyes of a woman. Byron and Ravenna

This year marks the end of the bicentenary of Byron’s death, about which it is difficult to write something that has not already been written. Considering the numerous biographies about him, we run the risk of retelling the romantic hero, the adventurous poet with an undisputed reputation as a seducer, the father of three daughters, paternity (it seems) reliable only for two girls, and the complicated relationships with the different mothers. George Gordon Byron confirms himself as a talented artist, with a tumultuous existence, bitterly amputated by his death, which occurred at the age of 36, due to meningitis, a death perhaps a symbol of incompleteness and testimony of unhappiness. But if he who dies young is dear to heaven, as Menander said, Byron’s fame is well deserved: he was one of the greatest representatives of nineteenth-century English poetry and a prominent intellectual in the United Kingdom during the second Romanticism. He traveled extensively throughout Europe, in different countries, linking himself in particular to Italy and the city of Ravenna, where he lived and spent himself in the many years. He was a politician, poet and companion of the very young Countess Teresa Gamba Guiccioli from Ravenna.

George Gordon Byron was born in 1788 in London, the result of the union between Captain John Byron, nicknamed mad Jack, or Mad Jack – who in life contracted infinite debts, apparently sadly paid in France with a suicidal death – and a very young Catherine Gordon, a moody and choleric woman, who alternated bitter reproaches with sudden and unpredictable tenderness. However, he spent little time in the English capital: he spent his childhood mostly in Aberdeen, in the land of Scotland, in the company of his mother, afflicted by a lameness linked to a tendon . The numerous attempts to correct that physical defect, namely the contraction of the Achilles tendon that led him to limp, were of no avail. Although masked by a sort of original gait, the lameness caused George enormous psychic suffering, making him feel tremendously different from the others. The economic hardship of the family also weighed heavily: only the death of a great-uncle allowed the change towards a comfortable and reassuring existence, thus avoiding the very young Byron a life that probably could have been poor, perhaps even flat and colorless.

1798 therefore marked a significant turning point: he inherited substantial assets from his great-uncle, a noble title and thus became the sixth Baron Byron of Rochdale or a Lord. He was finally able to afford a proper education and leave London for Newstead, coming into possession of large estates. In 1801 he began attending Harrow School where he distinguished himself for an insatiable love of reading, but also for an intemperate and transgressive conduct. Friendships, loves and deep bonds with both Mary Ann Chaworth, a distant cousin, and John Edleston will belong to the following years. The later relationship was even reported as homophile, one of the many reasons that would later push Byron to leave England and travel long and often in Europe

In the eighteenth century, but also in the following century, cultural tourism for a British man of letters also represented a real training tour, it became the humus from which to draw inspiration for the exercise of writing: in addition to showing affection for the different and the unusual, the journey in itself allowed the English writer to weave relationships with politicians and men of Italian culture of the time. Baldini and Bolognesi tell it in great detail (E.Baldini Dante Bolognesi The call of Ravenna The city and its surroundings according to foreign visitors 1800-1960, Longo, Il Portico, 2015), offering us pages full of bizarre events, intense passions, multiple interests and rare curiosities.

Not only therefore the bond with Edleston, who died very young, became the subject of deep disapproval by British public opinion: there were also many criticisms for the relationship with his half-sister Augusta, known by the poet only in adolescence, with whom he seems to have had a daughter, Medora, in 1814, who will take the surname Leigh, Augusta’s husband.

The bond with Augsburg remained strong and deep over time, as confirmed by the letter sent to her in March 1819 from Venice.

My love, I have neglected to write to you, but what can I say to you?! Being away for three years, a total change of places and habits, has led us not to sharing nothing, except affections and bonds. I have never stopped and will never stop feeling anything but a bond, deep, which unites and will unite both, thus taking away the possibility of feeling true love for any other human being.

Less than three months later, in June 1819, overwhelmed by his passion for the Countess Gamba, Byron decided to leave Venice for Ravenna: it was the three-year period 1816-1819 that marked a deep furrow in the existential change that would follow his stay in Italy.

1816 marks the separation from his first (and only) wife, Lady Milbanke, with whom he had had his daughter Ada. Very few or even zero will be in the future, by the express will of Lady Milbanke, relations with the child. Lady Milbanke – who at first rejected the poet’s amorous offers – came from an aristocratic family, was learned and religious, gifted in mathematics, so much so that she was jokingly nicknamed by her husband the princess of parallelograms. It was she who definitively broke the bond with Byron when, pregnant, she learned of the incestuous relationship that her husband had with his half-sister Augusta. ( https://ilfoglietto.it/il-foglietto/6416-annabella-milbanke-ada-byron-e-anne-king-donne-straordinarie-nella-vita-di-lord-byron)

In 1817 Byron’s second daughter was born, Allegra, a little girl who had a short life and a very unhappy death due, it seems, to typhus contracted while growing up in the boarding school of the Cappuccini Sisters of Bagnacavallo where her father had placed her, against the wishes of her mother Claire Clairmont. The very young Claire, just over nineteen, was torn by the distance from her daughter and saddened by the insensitivity imposed by a cruel pact/barter, expressly wanted by Byron. Claire would have had to give up any contact with little Allegra and Byron would have taken on the commitment to provide for the education of his daughter, who had to grow up like a real Byron. Claire at that time did not have sufficient means of support for herself and for Allegra: ensnared by the fascination that hovered around the poet and at the same time not wanting to give up life with her little daughter, she fought as much as possible to find a less inhuman agreement. Manuela Mazza tells it well (Claire Clairmont Epistolario Edited by Manuela Mazza, Ed.Solfanelli, Chieti, 2014) in her touching text.

Claire tried several times, and desperately, to convince Byron to change his mind but was forced to give up. In the meantime, little Allegra grew up without authoritative and loving figures of reference, more or less entrusted to the care of housekeepers, servants, perhaps even affectionate, not lacking the kind attention of the Countess Gamba, with whom her father had a deep relationship that lasted until the poet’s death in 1824. Very beautiful pages have been spent on Allegra’s life (Iris Origo Allegra la figlia di Byron, Skira, 2014) and perhaps represent a very delicate form of compensation (posthumously) for a time of life bitterly amputated. The child grew up lively and joyful, but in the eyes of her father she was nothing more than a pretty toy, perhaps a pleasant creature, certainly charming, with character traits and features that recalled the Byronic origin, but which inexorably alluded to the existence of a mother, moreover dramatically distant. Allegra had become the object of contention between two parents, the territory where the anger and intransigence of both had earned an unfair space. If Claire did not resign herself to the continuous rejections, continuing to show herself in love, Byron refused the fruit of the bond, with a contemptuous and tenacious punctiliousness. All in all, he behaved as if he wanted to erase the existence of the fleeting relationship he had with Claire with Allegra’s departure and therefore a form of responsibility pertaining to his own paternity. A laborious and paradoxical compromise was achieved not only by putting an end to Claire’s amorous instances and her desire to build a family that included the child, but by bartering the exclusion of the child’s life from that of both parents with the custody of the little girl to the Cappuccini Sisters of Bagnacavallo. A place where neither father nor mother went to visit Allegra : only their mutual friend Shelley, who had become somewhat fond of this creature, sometimes went to meet her.

Manuela Mazza, in her very delicate Epistolary, has been able to recreate that particular atmosphere between Claire and George, she has transmitted to us the moments of courtship, the flattery that the woman adopted for frequenting Byron, her ambitions, an unspoken dismay generated by Byron’s continuous rejections and, above all, the inner torment for not being able to provide for her child’s needs by her own means. A text that allows, through a narrative plot structured in the happy formula of the epistolary, to intuit in depth how Byron was far from assuming even the slightest responsiveness at the parental level and how intimate and intense was the suffering on which Claire’s life will turn. Claire’s life will be initiated. His epitaph concentrates pain and guilt that by the will of the deceased must have sounded a warning and reproach, carved on the tomb in the Cemetery of the Misericordia of S. Maria in Antella, a few kilometers from Florence.

She passed her life in sufferings, expiating not only her faults, but also her virtues .

The English poet George Byron arrived in Ravenna, a city festively decorated for the anniversary of Corpus Christi, on June 10, 1819.An arrival that did not go unnoticed because the carriage, which Byron had built, on the Napoleonic model, contained a cot, a bookcase, a chest and a tableware. At the invitation of Count Guiccioli, the husband of Teresa, whom he met in April in Venice, and upon payment of a fair rent, the British poet settled on the first floor of Palazzo Guiccioli, in the company of a large group of animals as well as, of course, numerous servants.

Ten horses, eight huge dogs, three monkeys, five cats, an eagle, a raven and a hawk, which, as noted by his friend and poet Shelley, visiting two years later, moved undisturbed around the house, protagonists of mutual altercations, which it seems were also witnessed by five peacocks, two guinea fowl hens and an Egyptian crane who were mostly stationed on the staircase of the palace.

If his friend Shelley could not hide his amazement, the people of Ravenna themselves were disconcerted by learning by chance of the existence of so many presences: the fame that surrounded a man of letters as bizarre as he was cultured and original was further amplified. It is difficult to establish the true role assumed by the πρόσωπον, a term that in the theatrical field maintains in Greek the meaning of “face” or “mask” is classic, thus implementing the concealment of the person: in all probability Byron nourished his character precisely on the demons that tormented him, on the restlessness that life caused him, above all on the restlessness, not without a self-imposed solitude, which exerted on many women of the time powerful charm and strong attraction. Somehow the fame of the character was fueled by the torment of the person himself and the attracted numerous criticisms and therefore not lacking the inevitable gossip, the English poet was at the center of the scene of a village such as we can imagine Ravenna at the beginning of the nineteenth century. For his part, Byron, sometimes annoyed by local gossip, returned malicious provocations with negligent annoyance, helping to further emphasize his reputation as an original character.

To the unkind comments and the not so concealed bewilderment of the people of Ravenna, Byron returned to sober and calculated indifference, an attitude that if on the one hand rebuffed gossip and gossip, on the other contributed to growing day by day that aura of charm and mystery that surrounded the English poet.

A bizarre transgression was not easy to marry with that sense of stability and obedience dictated by the local tradition, but every rule, including tradition, however protected and protective, required, almost in a sort of countermelody, the due exception. In fact, Byron wrote to Richard Belgrave Hoppner, in January 1820, a few months after his arrival in Ravenna.

I’m training very hard to learn how to fold a shawl (…) sometimes I get confused (…) and I put all the cavalier servants in agitation (…) it is a terribly moralistic place (Ravenna), in fact you cannot look after anyone’s wife (…)and if you go to the next door you are blamed and considered treacherous (…) The lover’s relationship has so many rules (…) because local women demand fidelity from the lover as a debt of honor. I have given orders to my rabble, six in number and passably battle-hardened, to defend themselves in case of aggression: on vacation days and great celebrations I will arm the entire team including me. (…) All these feuds, however, between the knight on account of his wife, and the troops on my liveries, are very tedious to a quiet man who does his best to please the whole world, and desires nothing but friendship and benevolence.

It must be said that Ravenna, although the object of visits by English writers and poets, was not at all a usual destination in the nineteenth century, because it was also difficult to reach. Harsh enclave or place of suggestions, it still remained distant from more traditional and famous destinations such as Venice, Rome, Naples and Florence. Chosen as far back as the V^ century A.D. as the capital of the Western Roman Empire, will confirm over time how much the isolated position surrounded by marshes, very difficult to conquer, will be able to offer security. Nevertheless, Byron’s stay enlivened this place, friendships and bonds were created and, above all, an active participation in the political life of the time was born: the poet became an American Carbonaro by making his home available as a weapons depot for the Carbonari of Ravenna. From the beginning of his stay, the relationship with the Countess Gamba will give stability to his wavering: after a rather disorienting impact, Byron will end up winning a sort of benevolence from the locals, a population that he defines as strangely frank, excessive as well as pugnacious. For Byron, the people of Romagna were even the best mercenaries that could be found, and he was not surprised even by the murders among the locals, usually daily killings, perpetrated some for amorous passion, others for interests related to property.

Original and generous, intemperate and intolerant of any form of authority, but pervaded by deep feelings of freedom and justice for the weakest, Byron fully confirmed, with actions and behaviors, that trait of originality that his biographies have always handed down to us. . The love for writing on which he tenaciously nourished himself would never abandon him: in the silence of the night his narrative images were born and from the memory of Dante Alighieri and Giovanni Boccaccio he grasped hidden suggestions. A lover of nature and the pine forest, where he often ridden, even in the company of the Countess Guiccioli, he assiduously frequented the local salons, where he was courted, honored, even pampered for his elegant and precious clothes, he a true representative of dandyism.

In one of the letters written to Augusta Leigh, in July 1819, all in all he admitted that he had found a sort of pacification, that he felt that something calmed him and therefore in some way aroused his interest. In essence, it really seems that he lived that time of life with a more intense sense of involvement, missed in the days of his past.

I have my horses, and they gallop splendidly through the forest, and then I also have my carriage, and the sea, and my books, and this lady; so time passes. I really like riding, I have always liked it outside England: I hate your Hyde Parks, and the tracks, I need woods, plains or deserts in which to wander, while I hate knowing in advance the road to take or being interrupted by your damn road signs, or by a peasant who shouts demanding two pence at a crossroads or in front of a fence. . Even the role of cicisbeo, a love custom of the time, all in all intrigues him: while validating his world and English origins as the best, he cannot help but be mixed with local customs. He does not show embarrassment, much less a hostile rejection, rather he navigates within a benevolent and almost condescending curiosity. While blaming the inconsistency of the figure of the cicisbeo, he conforms to it, at least in appearance: in this way he mimics a form of adaptation that allows him to ingratiate himself with the favor of the ladies and not to antagonize his rivals too much in love. In fact, the cicisbeo was nothing more than a sort of cavalier servant totally dedicated to the lady with whom he had intertwined the love affair, with the tacit consent of her husband (of the lady herself). It was therefore not a trivial damsel, merely caring: he was a kind page, with constant attention, a very significant figure in the love triangle that was in force at the time. The only condition set was that the substance of this form of love triangle should not be distorted: a strong and true feeling should not creep between the lady and the knight servant, thus capable of sinking the insignificance of the previous marriage bond. At first Byron complied with it but when the passion for the Guiccioli Countess turned into a stronger and more engaging feeling, also due to evident affinities of interests of both, the cards were shuffled so to speak and Teresa Guiccioli asked for separation from her elderly husband, a separation granted on the condition that the Countess returned to her father’s house Byron was a tormented, disputed and elusive man, he carried an inner storm and a dissatisfaction harbinger of restlessness. Perhaps it becomes easy to suppose that the person inside the well-known character masks better than others because his existence, although short, seems in itself a paradox: he declares it first of all in 1812 by stating that he woke up already famous the day after the publication of the first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

Byron’s stay in Ravenna is also able to tell us a lot about the soul of Ravenna, which Byron interprets in his own way: he lives it in excesses and rejections, he distances himself from them in the face of constraints, he becomes a participant in promoting attention to political struggles. In his correspondence with John Murray he responds in an open and enigmatic way at the same time to his request for a book on the customs of the Italians: it may be that I know more than most Englishmen because I have lived among them and in some areas of the country where English people had never lived before. I am talking mainly about Romagna and in particular about Ravenna but for many reasons I do not feel like publishing something on this subject. I have lived in their house, in the intimacy of their families, sometimes simply as a friend of the house, sometimes as a friend of the lady’s heart, and in no case do I feel authorized to write a book about it. Their morals is not ours, their life is not ours, the ways of thinking, of living are so radically different that I would not know how to illustrate a people who are at the same time sober and wasteful, serious in nature but buffoon when they have fun, capable of sudden and at the same time lasting impressions and passions, something that is not found in any other country and that for the moment does not have a society as can be seen from their comedies.

And yet, as Yourcenar herself later pointed out (…) there is no other city where the hiatus between inside and outside, between public life and the secret solitary life, is more affected. ( https://altritaliani.net/un-libro-una-citta-ravenna-e-marguerite-Yourcenar/ ) The city of Ravenna will become, between conflicts and loves, a place of the heart and mind in Byron’s personality, before his death in April 1824 in Greece. Strong political passion led him to join the Carbonari, favored by his friendship with Ruggero, Teresa’s father, and Pietro Gamba, both conspirators. Byron joined the Carbonara sect of American hunters, participating with his usual generosity in secret meetings. Thus he nourished not only the legend of a passionate mistress, but also that of a libertarian spirit, who in addition to supporting local causes will sacrifice in the name and on behalf of freedom the immense advantages of his condition, luck and genius . During the Ravenna period, he will never fail even the close bond with his natural sister, nicknamed Gus, the result of the previous union of his father Jack, souls who have kidnapped each other, somehow complementary to each other. Augusta, was, with Teresa Guiccioli, the woman who best knew how to convey the simplicity of a family warmth that the writer needed. On the other hand, that form of instability and restlessness, a salient trait of the poet’s personality, always took him elsewhere, pushed him in search of new places and unusual encounters, but they were also the most powerful spring that led him to write in the frequent form of self-representation.

The city of Ravenna is often associated with the life of the poet, especially in this 2024 that marks the bicentenary of the death of the English nobleman, so much so that the Ravenna image in which Byron easily homologates himself seems even too obvious and seems rather to enhance the climate of a (too?) past time that almost seems to insist on wanting to intertwine with its own recent past. The best narrator of a place is always the traveler who, unlike the tourist, manages to reciprocate that sort of mute dialogue, but eloquent at the same time, that is established between the eyes that look and things when they are seen.

Few cities in Italy offer more objects of interest to an antiquarian, a philosopher, a poet than does Ravenna, but its geographical position, which places it off the beaten track, makes it more let it be avoided by the general mass of foreigners who travel through other parts of this beautiful land. The Englishman more than any other people carries with him the habit of his own country: it seems that he does not travel so much for the purpose of studying the ways of others but rather to defend and show his own.

A man of letters, a poet, but above all a man of action, attentive to that spirit of discontent and insubordination – which smouldered under the ashes and sometimes ignited in sudden fires – Byron participated in the political struggle by making his own the sense of rebellion and the need for justice of those around him. The literate Byron does not differ from the political Byron, he interfaces with life that is fighting, fighting and participating as a companion.

In recent years, particularly in the period of the visit I am writing about, the whole district and Romagna in general have been the most restless and rebellious part of Italy. Freedom, justice and fraternity (…) are expressed in an anomalous amount of crime and insecurity for which they have taken root.

There is also and in some way Byron emphasizes it a contrast between the city of life and the city of memories, of the monuments of the past, between the city that you travel, in which you live the few or many days of the journey and in which the inhabitants live their human existence, and the hidden city, the one for which the journey was made, the literary one. The pages of writers and poets who have dedicated their works to Ravenna are full of this antinomy. It is impossible not to remember Gabriele D’Annunzio who wrote two lyrics about Ravenna, setting it in the memorable series of the cities of silence. The past that inhabits Ravenna comes from afar, from a world with which there is no longer contact (…) Ravenna whispers the intimate essence of the solitude of a world so desolate that only the sun, the fog and the wind seem to be at home. All the advantages of modernity have not, however, taken away much of that profound poetry that touched the hearts of Dante and Byron. But for Byron perhaps those ghosts were not part of the melancholy of the memory of the hidden city, they were part of the living city: truly the English poet represents the new attitude of those who look at the world from and within Ravenna. He finds in Dante a strong consonance, common feelings and destinies. Like Dante, Byron had had to leave his homeland even if for him, exacerbated by criticism for his conduct of life, it had been a voluntary choice. But he will continue to like Italy and Ravenna will remain a place of the heart.

With all its sins I have to say/that I like Italy that I like

Seeing the sun shine every day/ And the vines not planted on a wall

but clinging to the land / work pylons where people flock

when a dance closes the first act/among reddish vineyards as in France

(Keats Shelley Byron The boys who loved the wind Edited by Roberto Mussapi, Feltrinelli, Milan, 1996)

Editor’s note. The author addresses a heartfelt thanks to the Solfanelli Publishing House for the courtesy and availability shown. Equally heartfelt thanks are addressed to the staff of the Oriani Library in Ravenna for their kindness and care in making available very rare texts during the research.